How to Develop a Fundraising Plan

1. Create a budget

The first step is to create a working budget. A budget is simply a list of items on which you will spend money (expenses) and a list of sources from which you will receive money (income).

There is a simple process for budget preparation that most non-profit organizations can use effectively. The process takes into account the largest number of variables without requiring extensive research or developing elaborate spreadsheets. In some organizations, a single staff member prepares the entire budget and presents it for board approval, but this is a large burden for one person. Therefore, the method presented here assumes that a small committee undertakes the budget process.

Task one: expenses vs. income

The budget committee should first divide into two subgroups: one to estimate expenses and the other to project income. When these tasks are completed, the subgroups should reconvene to mesh their work.

Estimating expenses

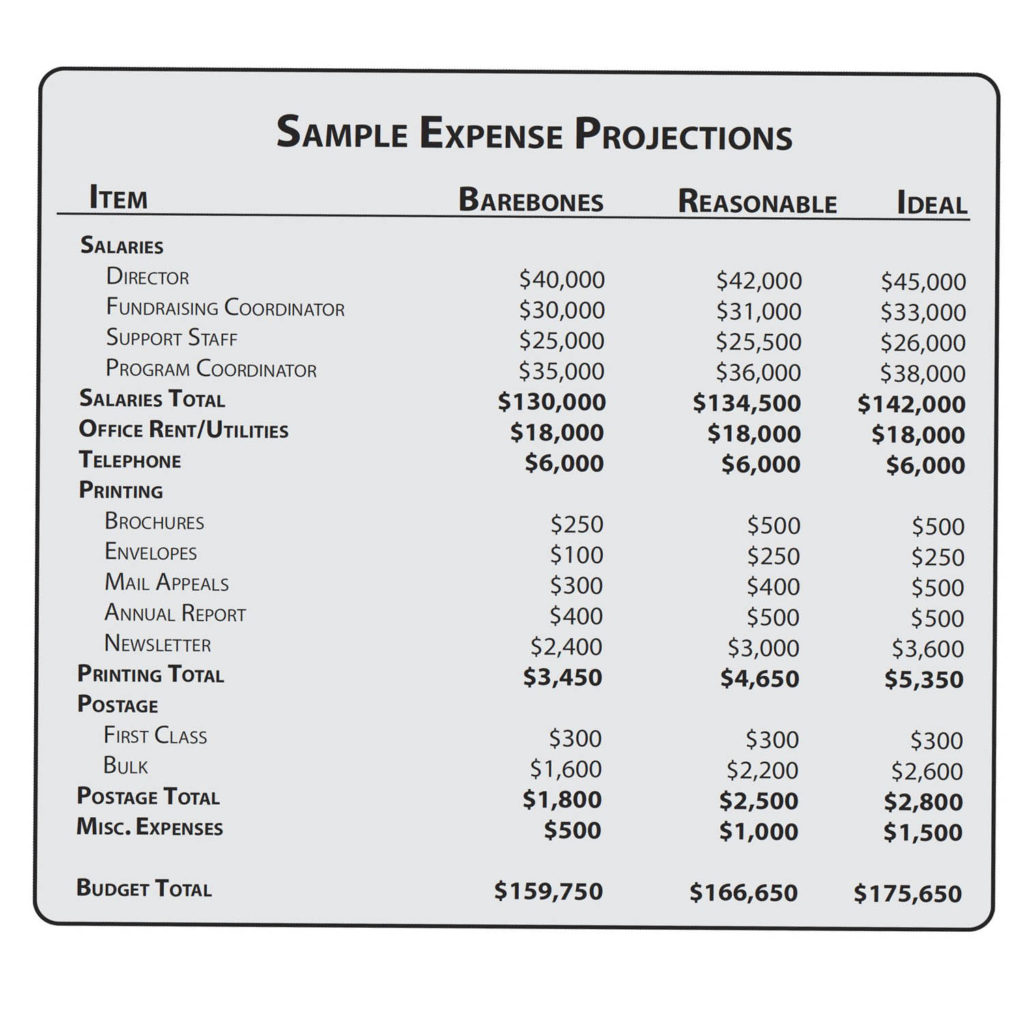

The group working on the expense side of the budget prepares three columns of numbers representing “bare bones, “ “reasonable” and “ideal” expense figures. The “bare bones” column spells out the amount of money the organization needs to survive. These items generally include office space, minimum staff requirements, postage, printing and telephone. This column does not include the cost of new work, salary increases, additional staff, new equipment, or other improvements.

Next the group prepares the “ideal” column, how much money the group would need to operate at maximum effectiveness. This is not a dream budget, but a true estimate of the amount of funding required for optimum functioning.

Finally, the group prepares the “reasonable” column: how much money the group needs to more than simply survive and be able to accomplish good work. These figures should not be conceived as an average of the other two columns. For example, an organization may feel that to accomplish any good work, the office needs to be larger, or to maintain staff morale, the organization must raise salaries.

Because higher rent and increased salaries are not necessary to a group’s survival, they are not included in the “bare bones” budget; however they are important enough to the organizations’s work to be included in the “reasonable” budget.

The “bare bones,” “reasonable” and “ideal” columns give the range of finances required to run the organization at various levels of functioning.

The process of figuring expenses and income must be done with great attention to thoroughness and detail. When you don’t know how much something costs, do not guess. Take the time while creating the budget to find out.

Fundraising plan

Veteran fundraiser Gary Delgado says there are four steps to successful fundraising: plan, plan, plan and work.

Fundraising planning is neither difficult to explain nor difficult to do. Not only is planning three-fourths of successful fundraising, it is also true that one hour of planning can save three hours of work. But the final and most important truth is that planning does not take the place of doing.

There are five steps to developing a fundraising plan.

Five steps to develop a fundraising plan

- Develop a budget.

- Determine the total amount of money to be raised from individual donors.

- Set income goals for different groups of individual givers.

- Decide how many donors you need to meet your goals, and select the best strategies.

- Put the plan onto a timeline and fill out the tasks.

Projecting income

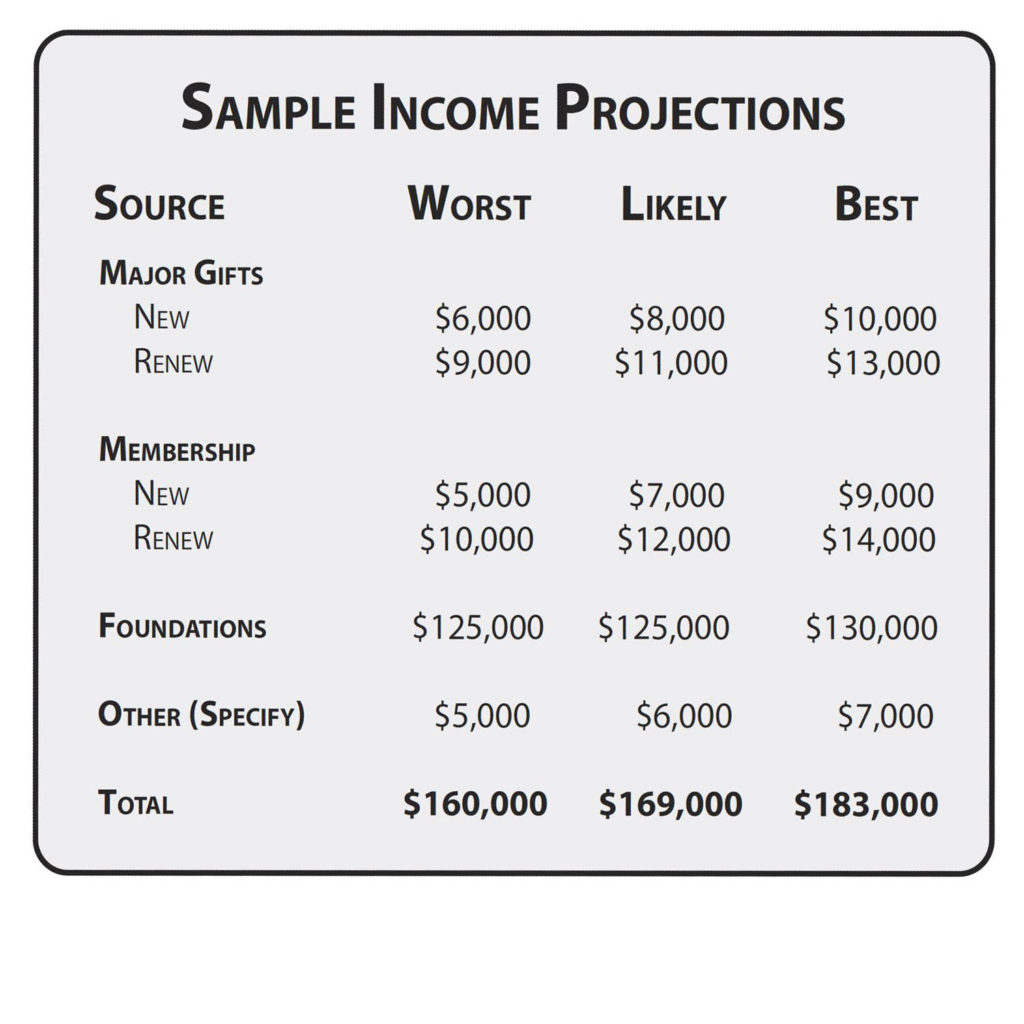

At the same time, the other sub-group should be preparing the income side of the budget. Crucial to this process is a knowledge of what fundraising strategies the organization can carry out and how much money these strategies can be expected to generate. The income side is also estimated in three columns, representing “worst,” “likely” and “best.”

To calculate the income projection labeled “worst,” take last years income sources and assume that with the same amount of effort the group will at least be able to raise this amount again. In case of foundation, corporation, or government grants it may be wise to write “zero” as the worst possible projection. Determine the “best” income projections next. These figures reflect what would happen if all the organization’s fundraising work was successful. Again, this is not a dream budget. It does not mean assume events that will probably not occur, such as someone giving your group a million dollars. The “ideal” budget must be one that would be met if everything went absolutely right.

The “likely” column is a compromise. It estimates the income the organization can expect to generate with reasonable hard work, expanding old fundraising strategies and using successful new strategies, while expecting to experience some difficulties.

Figure all income categories on amounts you expect to earn from each strategy before expenses are subtracted. The expenses must be included in the expense side of the budget. Be sure that the group developing the expense side includes fundraising expenses in the total organization budget.

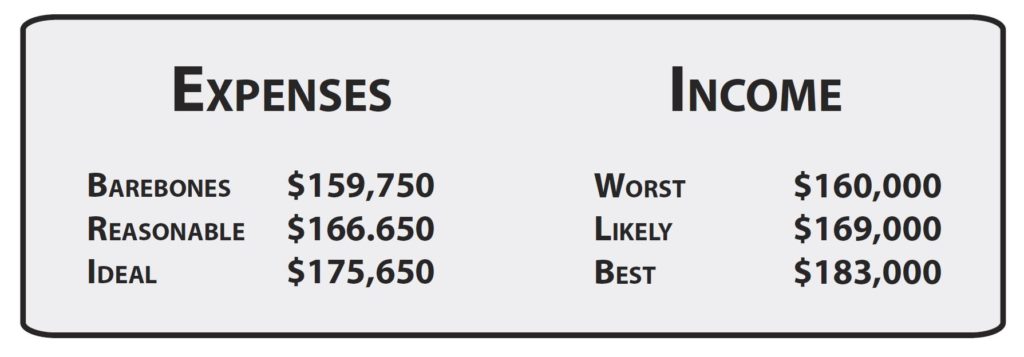

Task two: meet, compare, negotiate

Once income and expense projections have been completed, the two parts of the committee can share their results. When the income and expense sides of the budget have been figured separately in this way, there is less chance of giving in to the temptation to manipulate the figures to make them balance.

When the entire committee reconvenes, you hope to find that the “reasonable” column and the “likely” column are close to the same. In that happy circumstance those figures can be adopted as the budget with no more fuss. Occasionally groups are pleasantly surprised that their “likely” income projections came close to their “ideal” budget. However, compromises are usually necessary. In these cases, the expenses need to be adjusted to meet the realistic income potential, not the other way around.

When no two sets of numbers are anywhere near alike, the committee needs to find solutions. There is no right or wrong way to negotiate at this point. If each committee had really done its job properly, there is no need to review each item to see if it is accurate. However, with more research, sub-groups may discover other ways to lower expenses or add income.

2. Determine the amount to raise from individual donors

From the amount of money you must raise, subtract any amounts to be raised from strategies not involving individual donors, such as income from foundation, corporate, or government grants, product sales, fees for service, interest income, etc. The amount that remains is the amount that forms the basis of your fundraising plan for individual donors.

3. Set income goals

Now divide the amount of money to be raised from individuals into the proportions you can expect from different groups of givers.

- 60% of your money should come from 10% of your donors—major donors.

- 20% of your money should come from 20% of your donors—habitual donors giving through your retention strategies.

- The remaining 20% of your money should come from 70% of your donors—first time donors giving through your acquisition strategies.

Next, analyze your current donor list to answer the four following questions:

- How many donors do you have in the three categories listed above?

- What is your renewal rate? It should be around 66%.

- What is the organization’s strength in working with donors? Do you do a good job acquiring donors, but have a higher than normal attrition rate? Or, do you have a strong base of loyal habitual donors, but a lower than normal attrition rate (this would indicate a weakness in use of acquisition strategies)? Do you do a good job finding the top 10% of donors and regularly seeking upgraded gifts and major gifts?

- Has the number of donors to your organization grown, decreased, or stayed the same in the last three years? If it has decreased, you are definitely not doing enough acquisition and you may also have a problem with retention of donors. If the number of donors has stayed the same, you are either doing a good job with retention or acquisition but not both, because otherwise, you would see an increase.

This analysis will give you a clearer sense of the strategies to employ to meet your financial goals.

4. Decide how many donors you need

Match the number of donors you need to make your goals in each category with strategies that work best for reaching those donors.

5. Put it on a timeline

Put the entire plan, including all methods of income generation, onto a timeline and fill out the tasks. Voila! A fundraising plan is born. (This is not to underplay the amount of time it will take you to do these five steps—a planning committee of the board will need to meet two or three times to get a plan of this specificity accomplished.)

By using these steps, the fundraising planning process can be both simple and accurate.

Help create a healthy and sustainable West. Support WORC today.