How to Work in Coalitions

Build Your Own Organization First

When people are involved in community organizing to build power and win issues, the idea of forming or joining a coalition usually comes up.

Sometimes it seems like a shortcut – just link up with other organizations and there will be more power to win. While this may be true, coalitions can also be a distraction from the power-building organizing job that needs to be done first in your own organization.

This is so because of two important limitations of existing organizations: (1) many of these organizations are not themselves powerful, and (2) even where there are organizations with some strength, their purposes, goals, style and programs make it much harder than it looks to engage them in your organization’s issues.

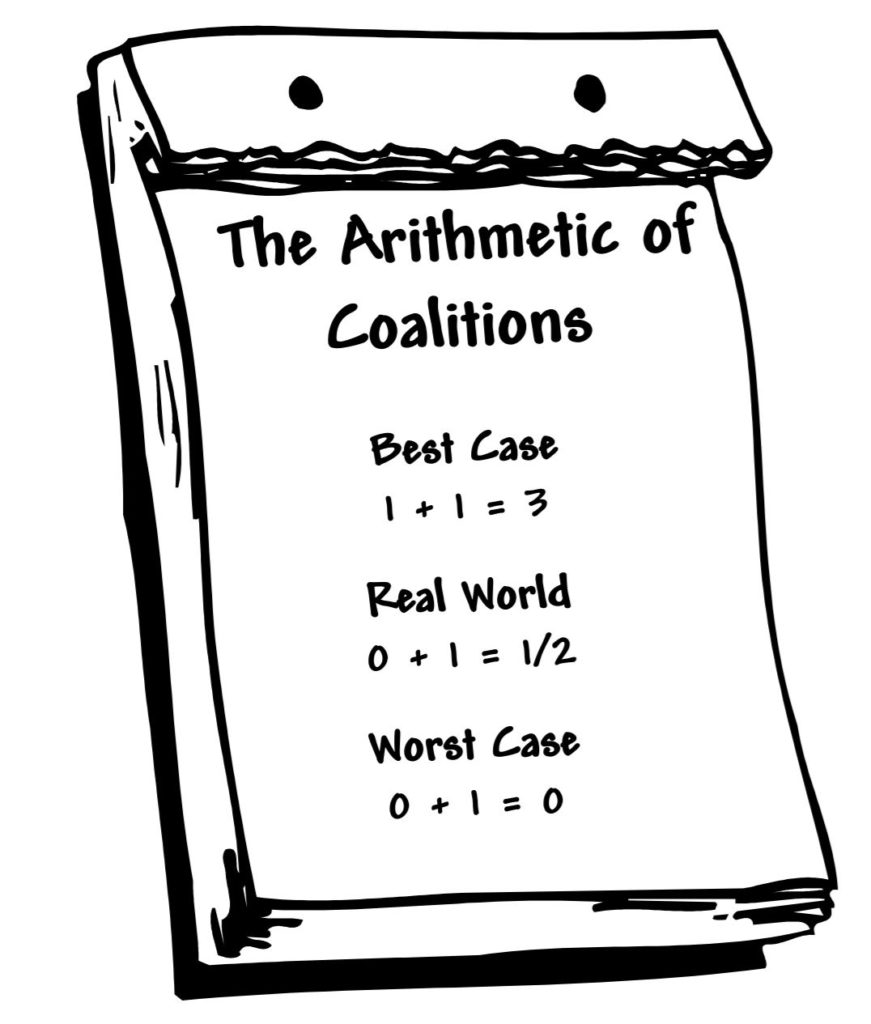

The real world arithmetic of coalitions has been aptly summed up by organizer Mike Miller as, “zero plus zero equals zero.” In other words, if you do not have any organized power to begin with you cannot join with another organization to create more power – especially if they are weak too.

Another way of thinking about coalitions is as a chain whose strength is measured not by its length but by its weakest link. So until you have built some people power, your energy should be focused on building your own organization rather than on forming coalitions.

But this does not mean that your organization should not build or join a coalition. You will need support. You are building relationships as well as power. Division and intimidation can be key tactics of your opposition. The way to approach a coalition is to think through the details.

What is a coalition?

A coalition is a group of organizations that come together for the purpose of gaining more influence and power than the individual organizations can achieve on their own. From a community organizing perspective, the reason to spend time and energy building a coalition is to amass the power necessary to do something you can’t do alone.

Coalitions come in a variety of different forms. They can be permanent or temporary, single or multi-issue, geographically defined, limited to certain constituencies (such as a coalition of farm groups), or any combination of the above.

Advantages to working in coalitions

Win together what you can’t alone. Complex issues often require large numbers of people and many resources to win.

Build your organization. The best coalitions make your own work more effective, expand the understanding and experience of your members, and provide opportunities for your leaders to develop their skills.

Increase and share resources. If the coalition’s issue is central to your organization, you may directly benefit from additional support and funding, and share resources to overcome deficiencies. The sum is often greater than the parts.

Broaden your scope. A coalition may provide the opportunity for your group to work on state or national issues, thus expanding the scope and impact of your work.

Learn and acquire new skills. By participating in a coalition you can learn from others and acquire new skills.

Overcome barriers of culture and history. A successful coalition can forge new partnerships and understanding among organizations and constituencies with a history of stressful interactions.

Disadvantages to working in coalitions

Distracts from other work. It takes time and resources to participate in a coalition. In the worst case, your work and the coalition’s work will both suffer.

Too many compromises. To keep a coalition together, it is often necessary to compromise and sometimes play to the least common denominator, especially when it comes to taking action.

Fail to receive credit. If all activities are done in the name of the coalition, groups that contribute a lot often feel they do not get enough credit.

Inequality of power. The range of experience, resources and power can create internal problems.

Loss of control. By joining a coalition, you are likely to lose some control over the message and tactical decisions.

Guilt by association. By associating with other members of a coalition, your group may also be associated with the negative aspects of those members.

Clearly, not all coalition experiences are positive, but when there is an important shared goal or issue, the benefits can outweigh the problems. The task, therefore, is to maximize the advantages and minimize the disadvantages.

Tips for successful coalitions

There are a number of tips to consider that will make it more likely that a coalition will stick together and succeed.

Use experienced coalition staff. Someone needs to take responsibility for the smooth operation of the whole coalition, and that person needs to be an impartial, experienced and savvy organizer.

Choose unifying issues. It is important to focus on one common issue where the members of the coalition can agree, and avoid the tendency to work together on each others’ separate agendas or issues.

Develop a realistic coalition budget. This budget should include staff time being contributed by each organization, so that the real costs of the campaign are understood.

Agree to disagree. Members of the coalition will not agree on all issues. Focus on your common agenda, and avoid issues on which you do not agree.

Play to the center with tactics. Developing tactics for a coalition is an area that usually requires compromise and a middle of the road approach. Space should be allowed for individual organizations to act independently and utilize more aggressive tactics, so long as they do not do so in the name of the coalition.

Recognize that contributions vary. There should be an honest and upfront discussion about what each organization brings to the table, and a recognition that although contributions may vary they are all essential to the success of the coalition effort.

Structure and clarify decision-making carefully. The coalition needs to be crystal clear about how decisions will be made and by whom.

Help organizations achieve their self-interest. Just as we organize people around their self-interests, so too must coalitions meet the self-interests of their member organizations. Organizations need to believe they are benefitting from a coalition.

Achieve real results. Coalitions must achieve concrete, measurable results that are clear to the member organizations. Otherwise, dissolve the coalition and form a coffee klatch.

Urge stable, senior board representatives. People who represent their organization in a coalition need to have a certain amount of experience and credibility. In grassroots community organizations, this is often a job for seasoned leaders.

Distribute credit fairly. An organization’s ability to survive and thrive often depends on the amount of public credit it receives. Coalitions that try to ignore this fact are headed for trouble.

Questions to consider before joining coalitions

You do not have to jump on board every coalition that walks in the door. Many organizations develop formal policies for joining coalitions and criteria for different levels of participation. Here are some questions to ask before joining a coalition.

- Who is behind the coalition?

- What is your organizational self-interest?

- Is the coalition necessary for what you want to accomplish?

- Will you be able to advance your own organizational agenda?

- Should the coalition be permanent or temporary?

- Will you have to compete with the coalition for resources?

- Is another level of organization and bureaucracy worth the time and resources?

- How can your leaders and staff participate?

- How will participating in the coalition build your organization?

The Give/Get Ratio

Too often, leaders in cooperative efforts feel like the hard work it takes to participate is out of whack for the benefits gained. We call it the Give/Get Ratio. For cooperative work to thrive, participating groups give time, money, expertise, staff and volunteer hours, and much more to the effort. Participating groups get the benefits of new relationships, learning, wider expertise and clout. The balance is never an exact tally: the nuances and sustaining benefits are different for each group…Also, remember that the sense of “give” and “get” will be impacted by differences of race and culture…

Frequently we jump into a coalition or alliance because it’s the right thing to do, and only later do we realize that it takes more effort than we can sustain. Sometimes we hesitate to express what our own group needs because we’re afraid of raising competitive tensions with other groups. But if we don’t ask, our participation will begin to fall away because we are not getting back what we need to sustain our involvement…

By paying attention to the Give/ Get Ratio, the cooperative effort can encourage each group to also plan to build their individual organization. For example, encourage each participating organization to define its self-interest for:

- Gaining members.

- Earning publicity.

- Encouraging new leaders.

- Adding new donors or resources.

- Developing new organizational capacity, such as new/expanded expertise, a new computer or additional staff.

When each organization puts its self interests on the table, all the partners can take those needs into account and talk about whether and how they can be met.

—Excerpted from Working Together: A Toolkit for Cooperative Efforts, Networks and Coalitions, by the Institute for Conservation Leadership, www..icl.org

Other Models of cooperative efforts

Coalitions are not the only way in which organizations can relate to and cooperate with each other. Sometimes it’s better NOT to form a coalition. For an excellent discussion of six different models of cooperative efforts, see the Institute for Conservation Leadership’s (ICL) publication, Working Together: A Toolkit for Cooperative Efforts, Networks and Coalitions. Here is a brief summary of the six models described by ICL:

- Network: formed to share information and learning on topics of common interest (e.g., Western Mining Action Network).

- Association of Organizations: a formal umbrella nonprofit that brings together organizations and/or individuals with common needs (e.g., Land Trust Alliance).

- Coordinated Project: frequently used by two or more distinct organizations to coordinate work and share resources on a specific issue or program they have in common (e.g., Blackfoot Challenge and Montana Nature Conservancy project to purchase and resell 88,000 acres).

- Campaign Coalition: brings together organizations committed to pursuing a single common issue in a jointly staffed campaign (e.g., Rocky Mountain Energy Campaign).

- Ongoing Partnership/Strategic Alliance: a long term, formal relationship among multi-issue organizations that provides mutual advantage (e.g., Northern Forest Alliance).

- Multi-Stakeholder Process: brings together organizations with diverse and sometimes conflicting perspectives on an issue, with the goal of discovering common ground and in some instances working together (e.g., Quincy Library Group).

Additional Resources

There are many good resources available that offer sound advice about building and joining coalitions. Here are several:

- “Building and Joining a Coalition,” by Lois Marie Gibbs.

- “Working Together: A Toolkit for Cooperative Efforts, Networks and Coalitions,” by the Institute for Conservation Leadership.

- “Coalitions and Other Relations,” by Tim Sampson in Roots to Power.

- “Coalition Management: A Checklist,” by the Hollyhock Leadership Institute

- “Coalition Activism – Rounding up the Unusual Suspects,” in The Activist’s Handbook by Randy Shaw

- “Building and Joining Coalitions,” in Organizing for Social Change by The Midwest Academy (Second Edition).

Help create a healthy and sustainable West. Support WORC today.